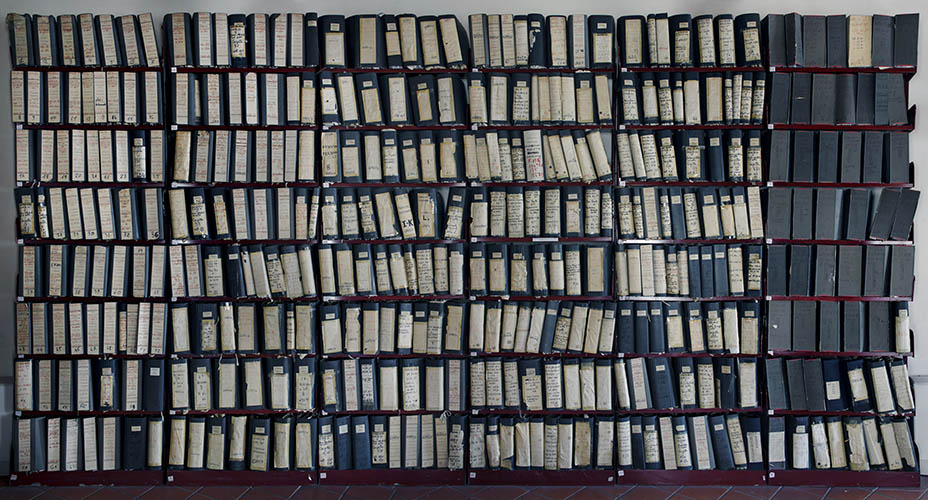

“What memories do places retain of the things that happened in them? It is a question hard to answer, yet it needs to be asked when looking at these photographs by Tommaso Bonaventura and Alessandro Imbriaco, realised for the research project curated by Fabio Severo. They represent places where a Mafia-style crime was committed—hence the title of the project, Corpi di Reato (“Corpora Delicti”). It could be a murder, building speculation, a house where a criminal at large has lived, or one still inhabited by a mobster; a whole suburb with a clan of gangsters ensconced in it; or courtrooms, archives of court cases, bunkers, legal evidence, statues of slain judges. These places, spaces and buildings, framed by the lens of Bonaventura and Imbriaco, are intended to indicate not just a criminal act, but also a visual presence: the Mafia is here, all around us.”

Marco Belpoliti, Domus, 2012

“Depicting the Italian mafias today poses the problem of what image to attribute to aphenomenon that has changed its face over the years, following decades of bloody struggleagainst the State. The scenario is drastically different now, and for years this has beenreflected in the changing strategy of the criminal organisations. There is talk of a mafiathat has almost stopped killing, as it mingles among civilian society and prospers in a greyarea where the signs of its presence cannot be sought merely in violence.Thinking about how the mafia has been documented in photographs over the yearsinevitably brings to mind the pictures by Letizia Battaglia, the most striking exampleof a visual chronicle and denouncement of the most violent period in the history of CosaNostra. Corpi di Reato (Bodies of Evidence) was born out of the need to seek a newimage of the mafias in order to capture in photographs the sense of the changing epoch inwhich we live. Letizia Battaglia’s pictures represent a here and now, an accumulation oftraumatic events that go to make up a picture of permanent conflict. Now that those armshave been partially laid down and the confrontation with the State has changed arena, it isnecessary to give a new meaning to the depiction of the territory and the documentation ofevents. Rather than a series of events, there is a need to show the state of things, the set ofconditions that characterise the forms of widespread presence of the mafias throughout Italy.Invisible mafia, white mafia, liquid mafia: many different definitions have been usedover the years to indicate these new forms of existence. Information itself on the mafia haslong appeared fragmented, far removed from the front pages in an age of a steady streamof episodes rather than great tragic events. However, this work does not pretend to be anexamination or an investigation of events, but is instead an expression of the need togather some of them together, helping to isolate them from the confusion of the news, andallow them to exist for a moment in the same place. It uses them as a map for travelling inItaly, connecting different events to each other to connect different parts of the country toeach other. It is a journey through Italy through the signs of mafia presence, through theirvisibility or invisibility.Viaggio in Italia (“Journey through Italy”) is also the title of the famous bookpublished in 1984 and curated by Luigi Ghirri, which subsequently became the manifestoof the Italian landscape school.That collective work of photographic exploration of the country was spawned precisely5by the need to rethink the depiction of the landscape, revealing the allure of the anonymouseveryday nature of the places depicted, far removed from the picturesque beauty andmonumentality of the cities.“The problem was thus to approach the landscape as an unknown and thereforeemarginated, excluded place”, Carlo Arturo Quintavalle wrote in his comments at thebeginning of the book. “A quest for a marginal, ambiguous fake, dual Italy, a substantiallyexcluded Italy, which is nonetheless the only Italy we know.”Corpi di Reato also begins by recalling the lesson of Viaggio in Italia, as summed upin the words of Quintavalle: following the traces of the mafia in our country means seekingforgotten places, which have almost disappeared; it means encountering the anonymous streetsof the cities and provinces where today’s mafia bosses live like normal citizens; or returningto the past, in the Castello Mediceo of Ottaviano, where the family of Raffaele Cutolo ruledlike kings thirty years ago, in an age in which bosses flaunted their power. Memories liveside by side with the present in the places explored, in the objects and in the landscape. Itis photography’s task to distinguish and compare them. Ghirri’s lesson was the rediscoveryof astonishment for the anonymous places encountered on an itinerary with no fixed route.Travelling in search of the signs of mafia presence, on the other hand, sometimes meansseeking a precise place – that street corner, that cornfield, that shutter – and then findingyourself looking at immobile spaces, at nothing; it means attempting to represent absence,emptiness. In this case remembering cannot mean commemorating, but becomes a testimonyof the transfiguration of things, the verification of the existence of a sign referring to whathas happened.The landscape sometimes appears scarred, at others indifferent: it may reveal or it maylie, and it is the job of the photographer to depict its ambiguity. The scar of the illegallybuilt housing on the Pizzo Sella hill overshadows Mondello like a corpus delicti, whilstthe setting sun over the Regi Lagni of Castel Volturno hides the poisons discharged intothe watercourses of the region. One feels the need to reveal the sound that produces thisimmobility, to observe it in order to discover the tiniest movement, to the point of trying toescape the fixed nature of photography by using video as well, employing the moving imageto try to suggest how a place may have appeared prior to the extraordinary event that hasmarked it forever, depicting oblivious everyday life before it is swept away.Corpi di Reato aims to continue exploring the many outer city areas in Italy, outskirtsthat are geographical but also mental: places situated on the edge, frequently forgottenepisodes that have lost their meaning, victims of oblivion that has made them eternallypresent, as though devoid of history.”

Fabio Severo, Landscape Stories, 2015